-

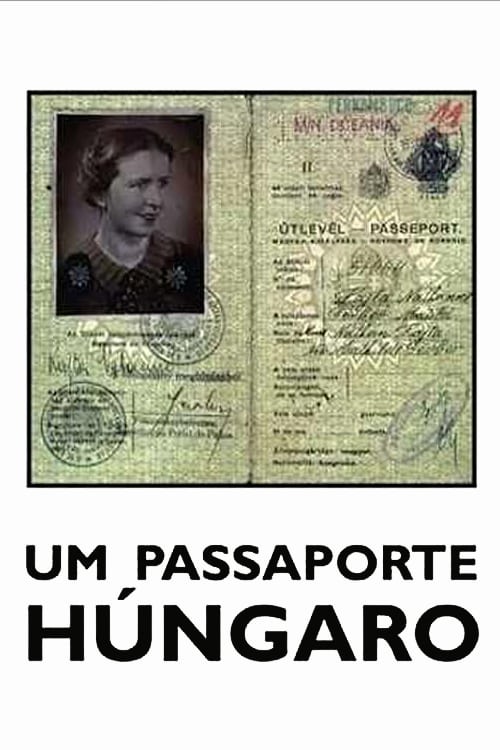

Habla tú. Narrativas del espectador en el cine brasileño

La rápida implantación de la tecnología digital ha permitido en los últimos años una transformación del concepto y de la inscripción social del cine documental en el ámbito de los discursos contemporáneos. En Brasil, el auge de los nuevos modos documentales se apoya en una rica tradición que apostó por la “participación” (artes visuales, teatro,…

-

La documentación y la memoria de lo efímero

El inicio de los registros generalizados de las artes efímeras, facilitado por la invención de los soportes videográficos en la década de los sesenta coincidió con un énfasis en lo performativo en el ámbito de la creación, es decir, con una acentuación de lo procesual, de lo presencial, en definitiva de lo efímero.

-

Kairos, Sísifos y Zombies

Reseña del espectáculo de L’Alakran, dirigido por Óskar Gómez Mata Kairos es el tiempo de la vivencia. No existe solo, existe siempre en compañía de Kronos, el tiempo de la sucesión, el tiempo de la historia, de la economía, el tiempo que se escapa continuamente. Kairos es el tiempo que se puede detener si uno…

-

La libertad y las delicias

Conferencia pronunciada en el Festival BAD, Bilborock, Bilbao, 22 de octubre de 2008 El título de esta ponencia apunta en dos direcciones: En el título hay, obviamente, una referencia a Voltaire. Las “Delicias” fue el nombre que el escritor francés dio a su casa de Ginebra. Para Voltaire las “delicias” no eran necesariamente las…

-

La danza que se toca

Sobre Solo a ciegas (con lágrimas azules) de Olga Mesa Olga Mesa ha compuesto una pieza escénica que funciona como un objeto, o más bien como una construcción cuidadosamente realizada mediante el agregado de pequeños pero sólidos objetos. Los objetos son inmateriales, existen sólo cuando el espectador asume que ya no está ahí para mirar, sino para…

-

Memory

Sobre la pieza del Living Dance Studio de Beijing La pieza forzaba al espectador a una reflexión sobre su posicionamiento en el campo de la mirada y a una toma constante de decisiones sobre cómo situarse en ese campo; en sentido literal, pues la duración de la pieza en su versión original (ocho horas) obligaba…

-

Cuerpo y cinematografía

José A. Sánchez e Isabel de Naverán, Cairon Revista de Estudios de Danza nº 11, 2008, pp. 7-11. El siglo XXI se inició con un renovado interés por los intercambios lingüísticos entre dos medios en principio excluyentes: el de las artes del cuerpo vivo y el de las artes de la imagen mediada. La preocupación…

-

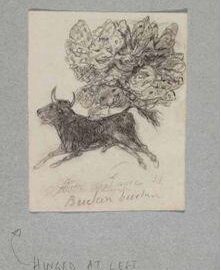

Volando a ras de suelo

Imagen y escritura en la creación española contemporánea. Conferencia presentada en el Ciclo: “Rite of Spring”, organizado por La Ribot y Live Art Development Agency. Centre d’Art Contemporain, Ginebra, 29 de febrero de 2008. Entre los dibujos más singulares que Goya dedicó al tema, figura El toro mariposa, realizado durante su exilio de Burdeos entre 1824…

-

En la recepción del premio Sebastià Gasch

Cuando recibí la llamada de Emili Gasch anunciándome la concesión del premio que lleva el nombre de su padre, pensé que se había equivocado. Hay tantos individuos con los que comparto el mismo nombre. Y más cuando supe que el primer premiado fue Charlie Rivel y que en el palmarés figuran varios payasos célebres. La…

-

Moviendo fijamente la mirada

Sobre Treintaycuatropiècesdistinguées&onestriptease, de La Ribot. 2007 Publicado en el DVD de la película. Ver la web de La Ribot. El texto propone comprender la pieza como un ejercicio de fijación de la mirada del espectador ideal por parte de la autora de las piezas y ahora realizadora de la película. El texto reflexiona sobre el modo en…

-

Perro muerto en tintorería. Los fuertes

Sobre la pieza de Angélica Liddell (2007) ¿Cómo una autora que se declara abiertamente contra el sistema y contra su sostenibilidad es capaz de producir una obra de teatro en su interior, sin por ello abandonar su crítica al mismo y a quienes en él confían, y sin embargo conseguir en esta producción su máxima…

-

La escena futura

Centro de Cultura Contemporánea de Barcelona. Ciclo I+D+I. 1 12 de julio de 2007. *** La escena del futuro es en lo esencial la escena del pasado, del mismo modo que son en lo esencial lo mismo la pintura o la poesía, medios todos ellos aparentemente arcaicos en la época de la realidad virtual, la…