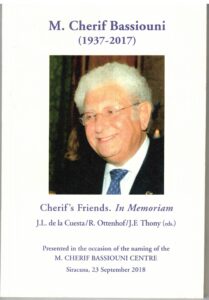

Luis Arroyo Zapatero President of the Société Internationale de Défense Sociale/International Society for Social Defence, AIDP Vice-president, and honorary president of the Spanish Group.

I had learnt of Cherif Bassiouni when commencing my doctoral studies. In the final convulsive years of Francoism, Marino Barbero Santos, in his professorial chair at the old university of Valladolid, explained what the AIDP was to the three students who would in good time have to become university professors. He described to us with such detail and enthusiasm how the patriarch of Spanish-American criminal Law, and disciple of Von Liszt, don Luis Jiménez de Asúa, had become Vice-President of the AIDP, recounting its survival after the war, and about the institute of Freiburg to which Marino Barbero had been invited, the first Spaniard under the august presidency of Hans Heinrich Jescheck, who are to be the next AIDP President after the Doyen Bouzat. He also spoke of a powerful Secretary General, enchanting in any of the languages that he spoke so perfectly, whom he also described in detail: a young official, decorated in the Egyptian army during the Suez war, successful European and American ventures, with the support of a diplomatic family, with a professorial chair at the DePaul University of Chicago and highly influential at the State Department and at the United Nations.

The destinies of both men coincided various times: in the first place, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Institute in Sicily, at Syracuse, which the professor of this eulogy directed and another one at Messina, in which Barbero Santos participated and at which I should have been; although I never appeared as a consequence of having to await a criminal trial before a criminal court on public order, a circumstance that had excluded me from any student grant or fellowship in Franco’s Spain. The Institute of Syracuse was admirably founded with total success. It is enough to see the photograph of the first promotion of the young international criminal-law student seminary of the time, where José Luis de la Cuesta and Christine Van den Wyngaert stand out, and to see that it has ever since been globally promoting the most expert international criminal lawyers.

My destiny led me to prepare my doctoral degree together with Hans Joachim Hirsch at the University of Cologne from 1975 to 1977, and I returned to Spain after the first elections in 1977. Barbero Santos, who was president of the Spanish group, organized the first AIDP congress, with the full support of the first democratic government. It was held with great success in Madrid and Plasencia. On that occasion, I became familiar with Jescheck and Vassalli. An ordinary edition in Spanish of the Revue was published, after a fierce debate with hundreds of messages exchanged between the Spanish group and the Secretary General, who had no wish to add to the languages of the journal, beyond the traditional English and French. What would they think today seeing that it is only published in English? After meeting on multiple occasions there are many of them I still wish to recall.

At the board meetings in Paris that I always attended following my election as president of the Spanish group after 2002, the final sessions were invariably a magnificent spectacle, as Bassiouni at his best addressed us all over the roundtables of the Maison des Avocats, giving us news, pointing out problems and seducing each and every one of us in so many languages. I recall a very unique night in which with deep emotion he gave us the news of the retrieval of the minutes of the meeting in Nuremburg at which the AIDP was reconstituted, by that time with Americans and Russians, pleasantly surprised for the first time with the simultaneous translation system of the proceedings of the international court, on 18 May 1946.

I think that the international congress at the Hague was certainly the most special moment of the professional life of Cherif Bassiouni, at which he presented the final report of his grand project: The Pursuit of International Criminal Justice: A World Study on Conflicts, Victimization, and Post-Conflict Justice, published in 2 volumes, in Intersentia, Brussels, Belgium, 2010. We were all backing him: judges from the International Court of Justice, from the International Criminal Court, and from the ad-hoc Courts and Tribunals, presidents of scientific societies, academic institutions. All there with him. He affirmed there his titanic work, of a lifetime advancing the convention against torture, the international criminal court and the civilizing effect of the United Nations and its institutions in a world of inexhaustible ferocity.

In Beijing, in 2005, at the congress that appointed José Luis De la Cuesta president he was troubled, both due to family reasons and to his journey to the volcanic mayhem of Afghanistan and the terrible realization of having lived through a great farce there.

In Doha, at the climate convention of the United Nations, he participated in the homage to Gao Ming Xuan, on the occasion of the award of the Beccaria Medal that the Société Internationale de Défense Sociale bestowed upon him. He was not optimistic, neither with regard to the abolition of the death penalty, nor with regard to the rest; he saw the world with great concern and left all of us concerned too.

The most emotional moment perhaps for me was his speech before the Spanish parliament, with the presidents of the parliament, the Supreme Court, the General Attorney of the State, at the award of the Beccaria Medal to him and to Mireille Delmas-Marty: an outstanding partner. It had grown late in the day and, after the laudatio that Muñoz Conde delivered, he left the papers on the table and in a Spanish tinged with Mediterranean overtones explained to us the reasons of a life dedicated to protecting the weakest through the progress of international law.

Bassiouni and his passionate works and sound academic grounding will not fade away and his example shines forth among us.